Aotearoa's pre-Internet web—an interview with Professor Tony Ballantyne

As Aotearoa New Zealand strengthens its Asia-Pacific relationships in the face of many challenges, we can look to deep historical connections for inspiration.

As Aotearoa seeks to strengthen its Asia-Pacific relationships in the face of many challenges, we can look to deep historical connections for inspiration. Professor Tony Ballantyne talked to The Context about how Asia-Pacific encounters have shaped our local communities and international connections.

Kiwi entrepreneurs venturing offshore, innovative migrants establishing businesses in our cities and provinces—today’s business stories include much to inspire New Zealanders with global ambition. But we can also look to our past for inspiration and even for deep international connections. Business networks between Aotearoa and the Asia-Pacific, after all, have long been woven into our history.

This history is not just one of colonies shipping wool, dairy and meat to the UK, but of personal and dynamic relationships stretching back and forth across the Pacific, says Professor Tony Ballantyne, prominent historian and Deputy Vice-Chancellor External Engagement at the University of Otago.

From tales of early trade emissaries to Asia, to explorations of the legacies that underpin our country’s many intercultural relationships, Ballantyne makes it clear that “Asia-Pacific communities in New Zealand have always been important connectors and bridges between worlds.”

As one example, Ballantyne mentions Chinese entrepreneur Chew Chong (Chau Tseung) who emigrated to Otago in 1867, via Singapore and Australia. Instead of heading inland to mine for gold with his compatriots, Chong made his way north. After discovering the wood-ear fungus (hakeke) growing profusely on native trees in Taranaki, Chong settled in the region and began a highly successful export trade of the medicinal mushroom back to China.

“Individuals like that have always been very adept at bridging and moving across cultural divides," states Professor Ballantyne. "And of course, their descendants and the families that come after them, have continued to build those connections.”

The pre-Internet web

A conversation with Professor Ballantyne will weave in and out of history, finding social context and drawing connections between the past, present and future. In his book Webs of Empire, Ballantyne does exactly that, reframing our understanding of historical encounters and relationships not as spokes in a wheel—with ‘Mother Britain’ at the centre—but instead as a web of linkages stretching across the Asia-Pacific. The nodes where these linkages met, whether in Gore, New Delhi or Singapore, helped to make and re-make each individual place and its relationships with the outside world.

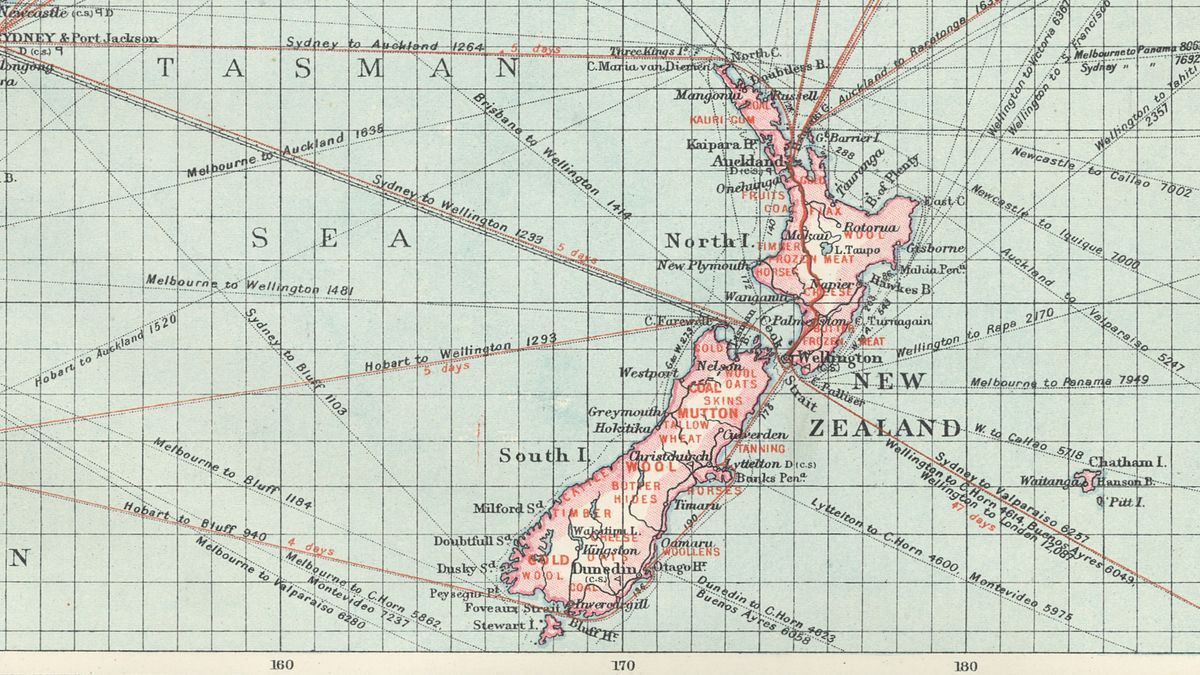

The map on the cover of Webs of Empire illustrates Ballantyne’s view nicely. “It comes from the Harmsworth Universal Atlas, a British atlas published in 1906” explains Ballantyne.

“One of the things I love about that map is that it imagines places and spaces and nations as being connected by the circulation and movement of things. You can see the lines of communication through the steamship and telegraph routes that connect to New Zealand, but you can also see the things that are traded.”

Travelling on these very routes was Kazuyuki Tsukigawa, a sailor from Nagasaki, Japan, who arrived in Otago in 1895. Tsukigawa captained the steamers on the lower Clutha River, becoming a prominent figure through his adventures and community involvement. In 1913, the local interest in his wedding was so strong that he and his bride Adelaide May Clarke had over 600 onlookers at their wedding.

Tsukigawa was not only the first Japanese person naturalised as a New Zealand citizen, but in 1936 he became our first unofficial trade ambassador to Asia when he returned to Japan armed with New Zealand products and a letter of reference from the New Zealand Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage.

“I’m really interested in the way those connections shift the demography of our society,” says Ballantyne “and how they shift the material culture we use, the food we eat, the languages we’re exposed to and the ways in which we think about the world.”

From family stories to engaging globally

Connecting New Zealand to the world has become part of Ballantyne’s own professional role. As Deputy-Vice-Chancellor External Engagement at the University of Otago, Ballantyne’s work includes building relationships with international partner organisations. He “feels spoilt” to be able to connect his scholarly work with his institutional leadership role in such a strong and clear way, but attributes this partly to an understanding of his own family history, an education that began early and close to home as he “sat in the corner of the room eating biscuits and listening to family stories.”

Ballantyne’s parents were born in the 1920s, his grandparents in the 1890s, and with almost 40 nieces and nephews he’s seen how his own family has expanded and changed, becoming a kind of microcosm of the wider social fabric. “I would say my parents came from fairly restricted worlds. But what’s interesting is if we look down at my nieces and nephews, many of them have had careers that are entangled with Asia in all sorts of ways. A number of them have married Asian partners, have Asian children and speak Asian languages. Asia has been a really important part of our family’s lives. And it’s not an unusual story - Asia is woven into the fabric of many families and I think it tells a story about New Zealand’s transformation.”

In thinking about history in this personal, connected and dynamic way, Ballantyne is also clear and upfront about “the centrality of race in that story” and the way in which the idea of New Zealand nationhood was often underwritten by anti-Asian sentiment. “If I think about my family story it’s breaking down and pressing against those exclusions and racisms. Obviously, we have a huge amount of work to do, but I think there are lots of reasons to be optimistic.”

For Ballantyne, this is where the Centres of Asia Pacific Excellence (CAPEs), where he is a Management Committee member, offer an opportunity for New Zealanders to engage and learn about regions that were previously presented negatively, misrepresented, or even caricatured throughout history.

“If we are to overcome those histories of racism, marginalisation and exclusion that were incredibly painful for a number of our migrant communities in the 19th and 20thcenturies, it’s really incumbent on all New Zealanders to reflect on our past and to work on building our cultural engagement and capacity. I think the universities can play a key role in that – whether through the teaching of language and cultures, through the support of research on societies and communities abroad, or building international connections with communities beyond our shores.”

Indeed, as we wrap up our interview, Ballantyne is himself preparing to head abroad, engaging partner institutions in the work of the University of Otago. This international engagement has been pivotal to his CAPEs work and his enthusiasm for its importance in providing business leaders, community leaders and students with tools to build connections and navigate relationships. “I think of it as a pro-active and constructive way of engaging with the world, something that’s much needed given the legacies that we have from those earlier colonial histories,” says Ballantyne.

“The more we can facilitate New Zealand’s connectedness with the world, the better for us - both in terms of the richness of our cultural life, but also in terms of the effectiveness of our business engagement with the world.”